Assignment

The Parts of the Puzzle exercise is a shape based project that requires imaginative problem solving within strict limitations.

Four 6”x8” compositions must be created while utilizing only three types of shapes: a circle, a line and a simple rectilinear shape.

Black construction paper, white Bristol board and painted gray paper should be used to employ an achromatic design. (Black paper may be made by painting Bristol board, similar to the gray paper.) Construction of the project will utilize rubber cement, acrylic paint (white and black), an X-acto knife, a ruler and a rubber cement eraser.

- No study may have more than six positive shapes.

- The same components must appear in each study.

- Any component may be repeated, as necessary.

- Any component may be enlarged or reduced in any study.

- If a shape extends beyond the boundary of a study, it should be cropped.

Preparation

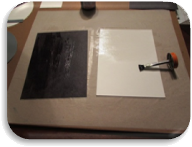

Knowing that I needed to create gray paper by painting white Bristol board, I started this process first. I cut approximately half of a large sheet of Bristol board for gray paper and left the remainder for my white shapes I would cut out later. Next, I took a large sample of white acrylic paint and a much smaller amount to black – approximately a 90/10 split – and started mixing the colors a little at a time with an old brush until I was happy with the shade of gray produced.

By utilizing a technique introduced by Dr. Giampa of painting vertically and then horizontally and cross-painting several layers in this manner a fairly solid gray was created. By brushing water into the mix and alternating the directional strokes, layer by layer, the actual brush marks were eliminated, little by little. I actually repeated this process a dozen times to smooth the surface of my gray paper as much as possible.

By utilizing a technique introduced by Dr. Giampa of painting vertically and then horizontally and cross-painting several layers in this manner a fairly solid gray was created. By brushing water into the mix and alternating the directional strokes, layer by layer, the actual brush marks were eliminated, little by little. I actually repeated this process a dozen times to smooth the surface of my gray paper as much as possible.

Halfway through my process, I noticed some inconsistencies in the paint. I wanted to eradicate these imperfections and rough areas before using the paper in my project so I smoothed the flaws with fine sandpaper before continuing with my layers of gray. One last attempt at removing brush lines was attempted by completing my last few repetitions with a sponge brush.

Case In Point

Chapter Four of Art Fundamentals: Theory and Practice by Ocvirk, Stinson, Wigg, Bone and Cayton was assigned to set the groundwork for this project as a study in shape. This chapter covered types, dimensions and expressive content of shapes as well as several compositional principles that apply to shape, such as harmony and variety, dominance, movement, balance, proportion and economy. Three-dimensional applications of shape were also mentioned.

Case

Depending on placement, shapes can create illusions of depth and dimensionality. Shapes are very expressive.

During the creative process, certain shapes can be planned and expected or develop themselves as the design evolves. Abstract shapes may morph into defined and recognizable shapes. Even negative space may become obvious shapes. All shapes have an outer edge – either implied or explicit.

Objective shapes are representational and more concrete than subjective shapes which appear much more abstract. Geometric shapes are very structured and defined – mainly consisting of a curvilinear and rectilinear contour. Biomorphic shapes, in contrast, are living, breathing forms; often they are thought of as natural and organic. The idea of implied, or amorphous, shapes is strongly connected to the principle of closure and indicates a shape that is not yet a shape – although, the human mind would argue otherwise.

Two dimensional shapes exist in any pictorial composition, although, through the use of the principles of organization, the illusion of three-dimensional mass may be created. Volume is the measurable space, or void, that will offset this mass and can also be implied in two-dimensional art. Planar shapes, however, are perceived as flat and have height and width but not depth. Equivocal space refers to the optical illusion of a shape seeming to change as the viewer’s perspective changes.

Shapes within a form will either work with the compositional layout or stand out from the design. Harmony may be achieved by producing shapes with similar characteristics while variety can be created with accents and changes to elements within a shape. Contrasting qualities of shapes suggest dominance and determine a viewer’s duration of attention. Subconscious association can also influence dominance. The angle or positioning of shapes (and other elements) can suggest movement. This movement can be toward the viewer, away from the viewer or simply within the image, from one area to another. The rhythm of movement can be smooth or jarring, quick or slow. Balance of one sort or another is almost always desired and may be achieved by the inclusion or absence of any elements and the development of many of the principles. By breaking down a subject of art into simple planer shapes, proportion and economy can become more manageable during the developmental stages of a composition. Objects in relationship to each other and their surroundings are more easily managed when containing less detail.

Artists may intentionally use certain shapes to invoke inevitable emotions from viewers. A spectator’s perception, imagination and sensitivity to form will all influence their appreciation of a piece of art.

Within three-dimensional artwork, mass is physical and measurable, as is volume, or areas within the piece that recede and hold space. Contours describe the shapes edges and the silhouette is a major example of a shapes boundaries. Secondary contours move the viewer’s eye around the work and join major contours together. The negative space of a three-dimensional sculpture is sometimes as important, if not more important, than the positive space as it moves the eye to opposite sides of an object and implores the viewer to experience the entire work.

In Point

By developing the bullets point of view, I’ve found deeper understand of each subject and happen to enjoy the process of personification. To that end, I employed that empathy to shape and three aspects of Chapter Four I found most important.

Type

As a shape, I can be defined or implied, abstract or representational, geometric or biomorphic. The beauty of being me lies in my ability to not only be all these things; I can also be several at one time! I may allow you to see my true nature or I may hide my contours and make you wonder if I am what I say I am. I can be rigid and mathematical or I can move and breathe just like you. I can even be both simultaneously or change right before your eyes!

Composition

However, you may want to be careful how you use me, who you put me next to and how often you duplicate me. My relationships are delicate and I can be quite temperamental. For example, if you want me to get along with all your elemental cliques, I suggest you keep some of us together. We like to mingle with family and friends; but if you start to clone us we can easily become bored and refuse to play nice. Some of us are dominant by being different but there is a balance to be found within this variety. My friends and I all have rhythm but it may not please everyone all the time. Like I said, be careful!

Emotion

If you upset me, I may not be predictable; then again, often times I am and you can use this knowledge to your advantage. Know your enemy! Scratch that. Know your observer (if you think you can). Their imagination, perception and emotions are influenceable, but only to a certain extent. To thine own self, be true!

Development

After reviewing the requirements, limitations and examples of this assignment, I had a vague idea of some personal elements I wanted to include and thought they would be instrumental in making my final design unique while staying within the guidelines. I was certain I would include circles of various sizes in each study, squares in alternating positions and sizes and straight lines, both horizontal and vertical, all the same width but of varying lengths.

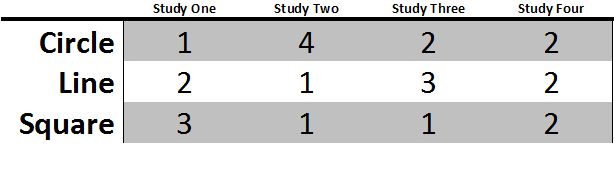

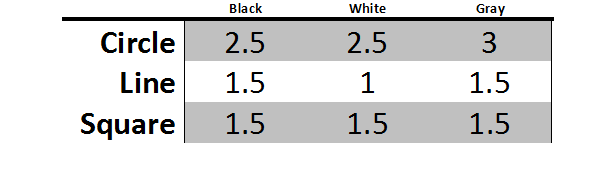

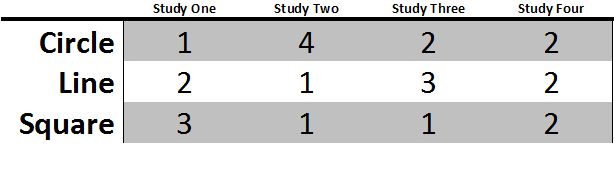

I decided I would include exactly six shapes in each study but I used a random method of assigning how many repetitions of each would occur in which study by laying out a grid with the shapes on the left and the study number on top.

By assigning one circle, two lines and three squares to Study One, I started a pattern that indicated Study Two would include four circles; however, since no study could have more than four shapes while still including a minimum of one of the two remaining shapes, Study Two could only include one line and one square.

This began a simple game of Sudoku, because Study Three and Study Four could only have two circles each. With three being the next logical number, Study Two was assigned three lines and left with one square. To round out the study varieties, Study Four was allocated two lines and two squares.

The resulting grid contained a happy coincidence of seven squares, eight lines and nine circles; thus satisfying an obsessive compulsive need for numeric order.

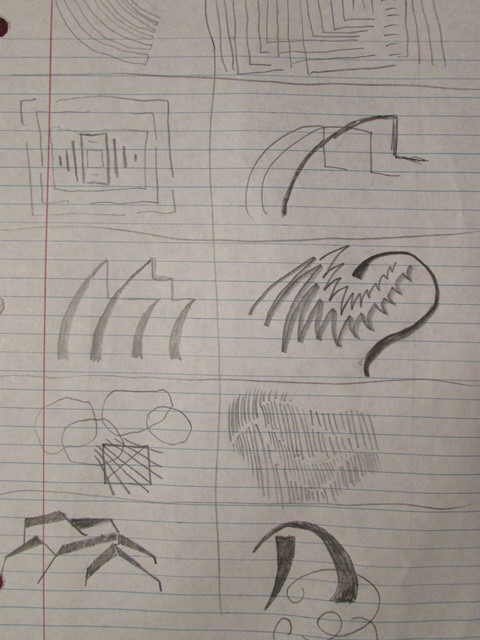

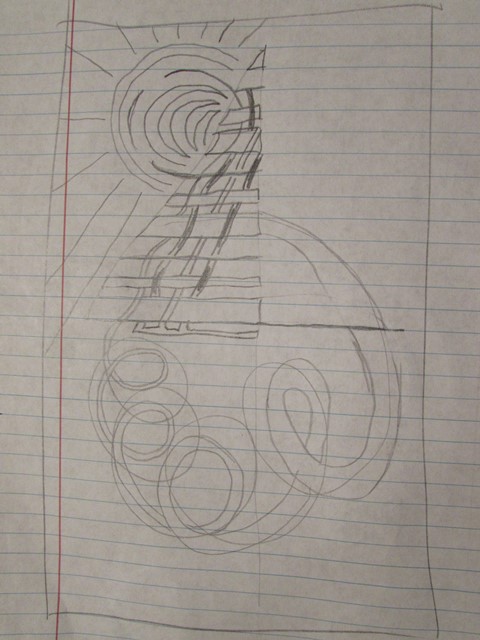

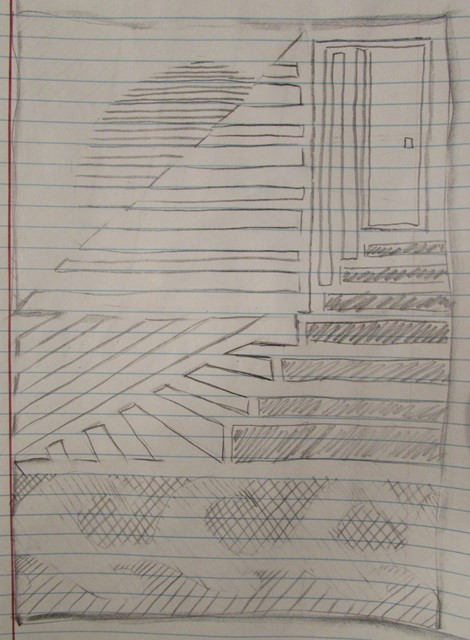

Thumbnail Sketch

One of my initial desires for this project was to complete the four studies in such a manner that I could create one complete composition out of the four individual designs. To this end, I started reverse engineering by sketching the completed, combined image and breaking the design into four separate panels during the process. However, I didn’t simply sketch a composition and divide it into four pieces.

First I reduced the entire sketch to exactly half of the required project size. By designing in this manner, I made my sketch a manageable unit that fit within one piece of notebook paper and could be edited and experimented with to scale.

I started with a square that would share space with all four studies and, just to add a unique twist (literally), I rotated this square 45 degrees. Continuing with shared shapes in mind, I added lines that would cross panels. This allowed me to connect Study One with Study Two and Study Three with one horizontal line and one vertical line; likewise, Study Three connected with Study Four with two horizontal lines. This finalized the self-imposed line requirements. The last shared element needed to be a circle, thus ensuring at least one example of each shape would cross panels within the final design. This was accomplished between Study Three and Study Four.

To balance the lack of lines on the left side of my overall image, I added a square to Study Four precisely where the vertical line existed in Study Three. The last shape needed in Study Four was a circle and an empty area in the lower right-hand corner lent itself perfectly for a medium-sized shape to extend outside the bounds of the panel. Similarly, I added a smaller circle to Study Three in a position that not only balanced the individual panel but offset the small square in Study Four, thus completing a second study.

To balance the lack of lines on the left side of my overall image, I added a square to Study Four precisely where the vertical line existed in Study Three. The last shape needed in Study Four was a circle and an empty area in the lower right-hand corner lent itself perfectly for a medium-sized shape to extend outside the bounds of the panel. Similarly, I added a smaller circle to Study Three in a position that not only balanced the individual panel but offset the small square in Study Four, thus completing a second study.

Next, I added an extremely large circle to Study One in the upper left-hand corner, which was intended to contrast with the many smaller shapes already included within the composition, harmonize with the overlapping circle in Study Three and Study Four and balance the opposing circle in Study Four. Two squares were needed to complete Study One and the first was included in the upper left-hand corner to extend off the panel and break up the large, flat area created by the gigantic circle. The remaining square was purposely reduced to arguably the smallest shape of all the studies and ironically shared space with the largest shape of all the studies. Set between the horizontal and vertical lines and diagonally between the conventional and rotated squares, this last element of Study One resided comfortably on top to the large circle and close to the center of the panel.

Study Two was left with a need to elegantly include four circles, the most shapes of one kind in any panel, while simultaneously maintaining a balance within the overall composition and executing an impartial image, strong enough to stand alone. Luckily, I had an idea for these four circles as soon as I noticed the numbers in my planning grid. While almost every shape in the other three studies were intertwined by means of overlapping shapes – the offsetting square and circle in Study Three and Study Four, respectively – Study Two would allow it’s four circles to float off the top of the panel from a free-standing position near the center of the design. The circles themselves overlap but are not connected to the other shapes nor are they allied with any other elements in the combined image. However, by wrapping around the line on the left side of the study and seeming to originate from the implied square in the lower left-hand corner, an economy and domination are produced concurrently.

Normally, I would never begin finalizing a project without attempting several variations, sketches and ideas. However, I was so inspired by the effortlessness with which this design presented itself and the simple complexity of which it was comprised, that I had no choice but to proceed.

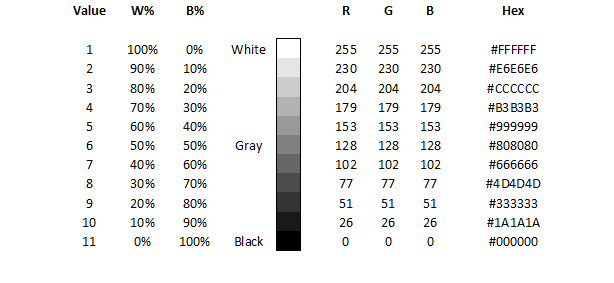

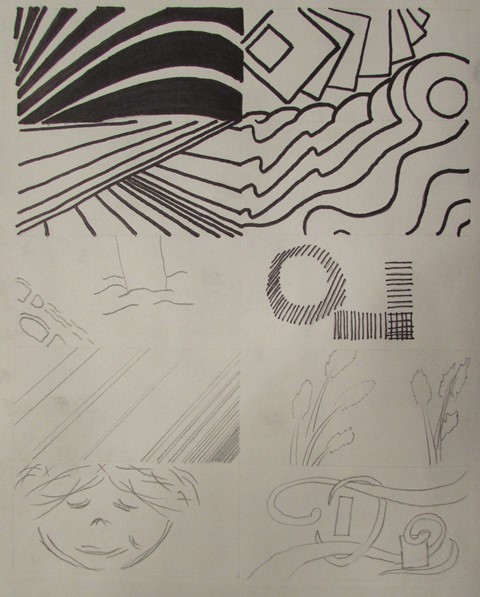

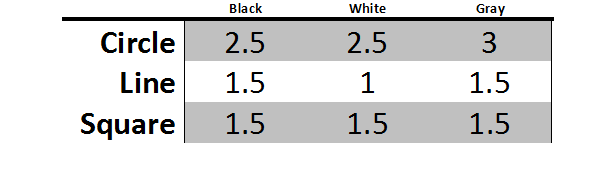

Prototype

Once all the shapes were included in each study and arranged in their appropriate locations, it was time to visualize the values and their contrasting and harmonizing properties. To determine which shapes should be black, white or gray I needed a sample of each shape in each color. I basically measured my sketch, cut out one black shape from construction paper and two white shapes from scrap paper. To simulate gray, I colored in one of the duplicate shapes for each individual component. Then it was a simple matter of moving the samples around over simulated backgrounds. It’s important at this point to mention that I planned on utilizing two black, one white and one gray background. This decision was based on a practical need to economize my limited gray Bristol board.

Once all the shapes were included in each study and arranged in their appropriate locations, it was time to visualize the values and their contrasting and harmonizing properties. To determine which shapes should be black, white or gray I needed a sample of each shape in each color. I basically measured my sketch, cut out one black shape from construction paper and two white shapes from scrap paper. To simulate gray, I colored in one of the duplicate shapes for each individual component. Then it was a simple matter of moving the samples around over simulated backgrounds. It’s important at this point to mention that I planned on utilizing two black, one white and one gray background. This decision was based on a practical need to economize my limited gray Bristol board.

If the shape arrangements within each panel while simultaneously appeasing a combined composition was a balancing act, then the value distribution of each study was the tight-rope in the center ring! To begin, I placed my gray background and one black background in the lower corners of my overall design because together they would weigh more than the black and white backgrounds in the upper corners.

Starting with Study One which was assigned a black background, the large circle was decidedly white for contrast. The line from Study One to Study two would become black to connect the panels and the background in Study One, since it overlapped the large white circle. The rotated square was made white to balance the study and the square in the upper left-hand corner was allocated gray, both to contrast with the white circle while tying the vertical line into the composition, as it was assigned gray as well. The tiny square was made black to stand out from the large white circle and harmonize with the black horizontal line.

Following the gray line into Study Three allowed me to change the value to black since it would overlap the gray background. The horizontal line in the lower portion of the study was white and stayed white as it crossed into Study Four. The white square from Study One was continued into Study Three and remained white while overlapping a black circle. Also overlapping this circle would be a gray line which crossed into Study Four above the white line. Lastly, the circle on the left of the panel was assigned a white value to stand out against the gray background.

Two things happened when Study Three combined with Study Four: first, the black circle became a white circle to contrast against the suddenly black background; second, the square on top of the white circle become black, for the same reason. The white square on the right-hand side of the study was made white to stand out against the black background and to compliment the other lone shape in Study Three: the white circle. Lastly, the circle in the lower right-hand corner was given a gray value to add variety to this panel while at the same time tying into the adjacent panels and to contrast with the overlapping white line.

In Study Two, the square was continued from Study Four as black that contrasts perfectly with the white background. Alternating gray and black circles gradually grow and float off the study starting with gray and ending with black. This allows the largest black circle to offset the black square and be divided by the black horizontal line. The gray circles provide unity and variety at the same time while the white background provides the illusion of space and atmosphere.

Construction

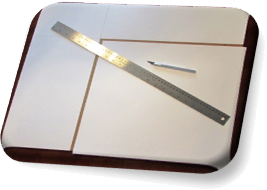

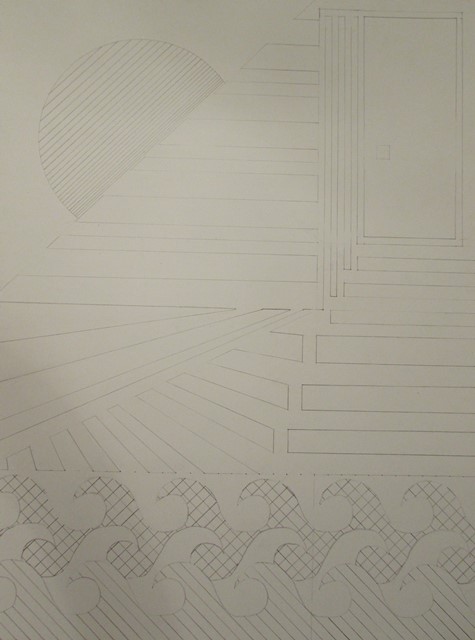

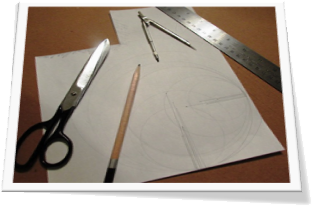

I measured a quarter inch border to cut shapes from the gray painted paper and used the same procedure to extract my gray background panel. For each straight-edged shape, namely the squares and lines, I used an X-acto knife and a ruler.  For each circle I cut the shape out with a pair of scissors, leaving a quarter-inch margin and then carefully cutting closer until an exact circle was removed. A 6”x8” section of Bristol board was cut as the background of each study, even the white panel.

For each circle I cut the shape out with a pair of scissors, leaving a quarter-inch margin and then carefully cutting closer until an exact circle was removed. A 6”x8” section of Bristol board was cut as the background of each study, even the white panel.

Because I started my sketch and sample to a 1:2 scale, all I had to do to create perfectly sized shapes was multiple my sample shapes by two. For each circle, the diameter of the sample was measured and then divided by two to find the radius.  The radius was multiplied by two and a compass was used on a scratch piece of paper to test the visual impact of the new shape. After confirming the new size was appropriate, the compass was used on the white, gray or black paper to create the final shape. (It may not seem important to go through the process of finding the radius as the new radius is simply the diameter of the sample shape; however, if I were to need to triple or quadruple the sample size, this procedure would be vital.) All the rectilinear shapes, squares and lines (which are essentially rectangles), were simply doubled in width and length. This method allowed my final composition to be a scale representation of its sketch.

The radius was multiplied by two and a compass was used on a scratch piece of paper to test the visual impact of the new shape. After confirming the new size was appropriate, the compass was used on the white, gray or black paper to create the final shape. (It may not seem important to go through the process of finding the radius as the new radius is simply the diameter of the sample shape; however, if I were to need to triple or quadruple the sample size, this procedure would be vital.) All the rectilinear shapes, squares and lines (which are essentially rectangles), were simply doubled in width and length. This method allowed my final composition to be a scale representation of its sketch.

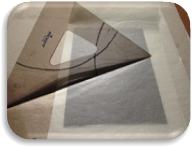

Once I had all of the appropriate shapes cut out of the black construction paper, white Bristol board and gray painted board, I arranged them together to visualize the final designs. To ensure each component was aligned correctly, I measured and documented guidelines to appropriately place each shape within its study.

Once I had all of the appropriate shapes cut out of the black construction paper, white Bristol board and gray painted board, I arranged them together to visualize the final designs. To ensure each component was aligned correctly, I measured and documented guidelines to appropriately place each shape within its study.

Employing the technique of applying rubber cement in a scoring method demonstrated by Dr. Giampa, horizontally on one element and vertical on the component to which it would adhere, each background, circle, square and line was affixed to each study until all four panels were complete. Smoothing the shapes to each other by covering the area with tracing paper and utilizing a drafting triangle to press from the center to the edges allowed each shape to be perfectly flat. Cropping shapes that extended beyond the limits of its panel occurred as necessary.

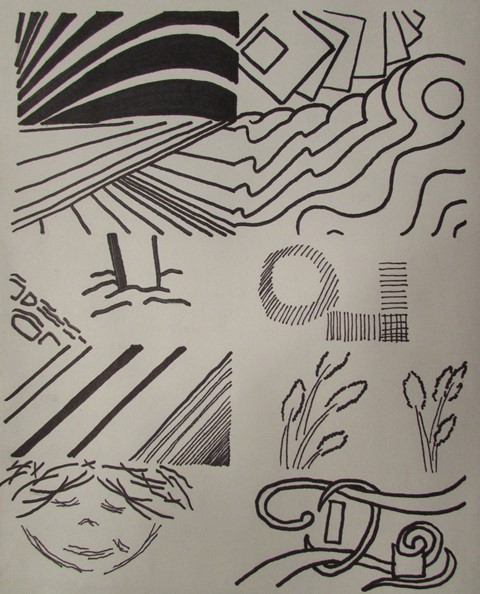

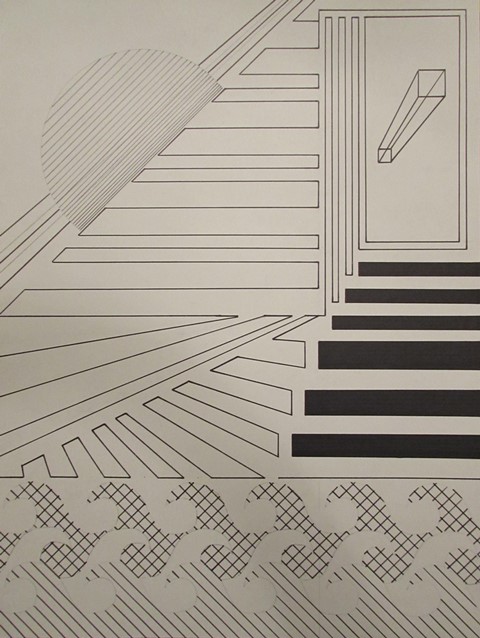

Completed Project

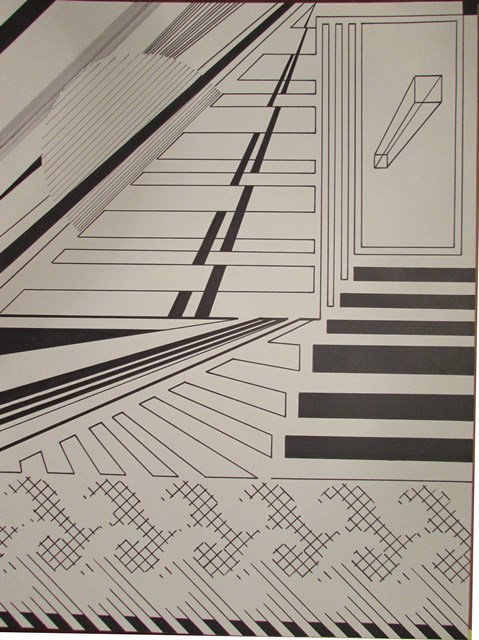

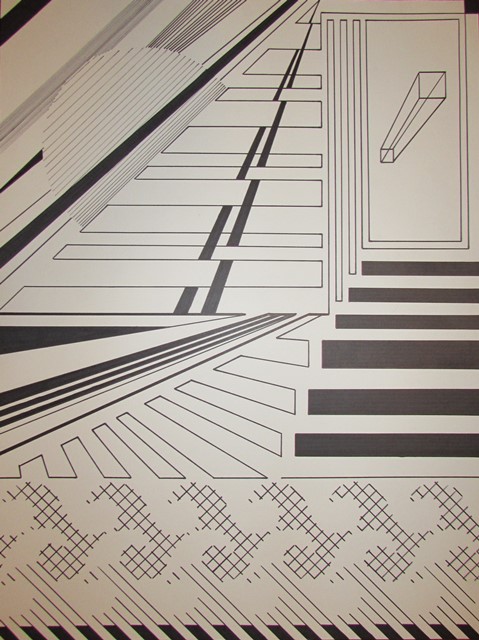

Puzzle Pieces

The final individual studies are each compositionally stable, interesting and independently successful.

Single Study

Additionally, the four studies can be combined to indicate a new, single design.

Complete Separation

My personal preference is to view the combined panels with some white space between each study.

View/Download PDF

Case In Point Mapping based on research by

Dr. Joan Giampa http://www.joanmariegiampa.com/teaching/my_research.html

Like this:

Like Loading...

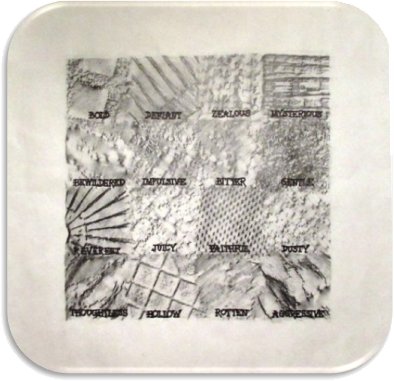

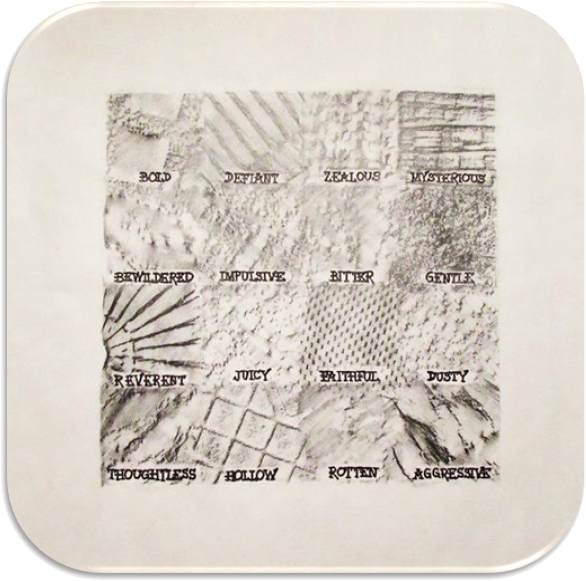

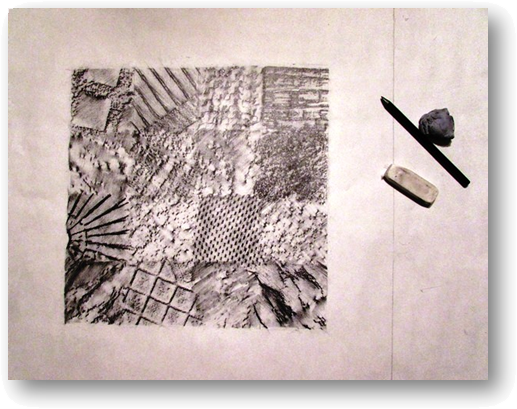

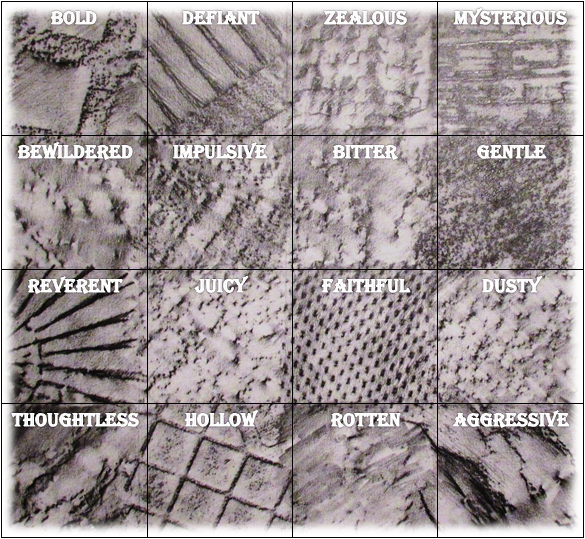

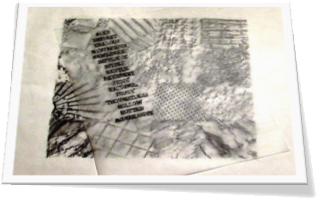

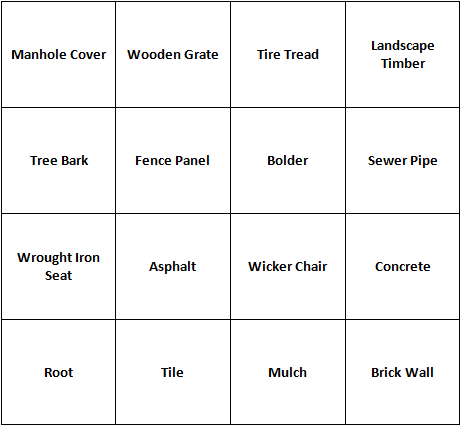

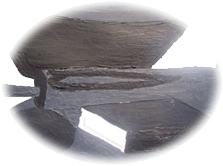

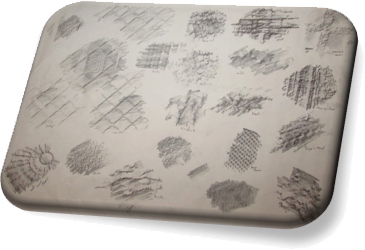

As I found each texture I was interested in, I took an initial rubbing with a 6B graphite pencil. I did this for two reasons: first, I wanted to make sure the surface I thought would produce a nice transfer actually produced a unique effect. In some cases I found the surface didn’t stand out or even transfer so I moved on. My second reason for the rough draft was to visual organize the patterns in my mind before deciding where within my grid I’d like the final rubbing to exist.

As I found each texture I was interested in, I took an initial rubbing with a 6B graphite pencil. I did this for two reasons: first, I wanted to make sure the surface I thought would produce a nice transfer actually produced a unique effect. In some cases I found the surface didn’t stand out or even transfer so I moved on. My second reason for the rough draft was to visual organize the patterns in my mind before deciding where within my grid I’d like the final rubbing to exist.